Joe Burrow is one of the bright young stars currently at the quarterback position in the NFL. He is the reigning Heisman trophy winner, NCAA Football National Champion and was the number one pick in the NFL draft this past spring. Unfortunately, with no offseason and zero preseason games due to COVID-19, he was at a huge disadvantage as a rookie quarterback. Despite these obstacles, he had been playing quality quarterback in his rookie season up until November 22nd, when he suffered an unfortunate season ending knee injury.

The Injury:

The injury happened on a 3rd and 2 play from the Bengals’ own 9-yard line. The Bengals lined up in a shotgun formation with 4 wide receivers. The Washington Football Team showed blitz and initially rushed 6. Montez Sweat, the Redskins defensive end, lined up on the right side of the line gets pressure first – Burrow sees him and steps into a throw, down the right sideline, to WR Tyler Boyd just before Sweat hits him in the upper body. Unfortunately, Burrow did not see the pressure from the inside of the line as defensive tackle Jonathon Allen makes his way through and gets blocked down directly into Burrow’s left knee just as he releases the ball.

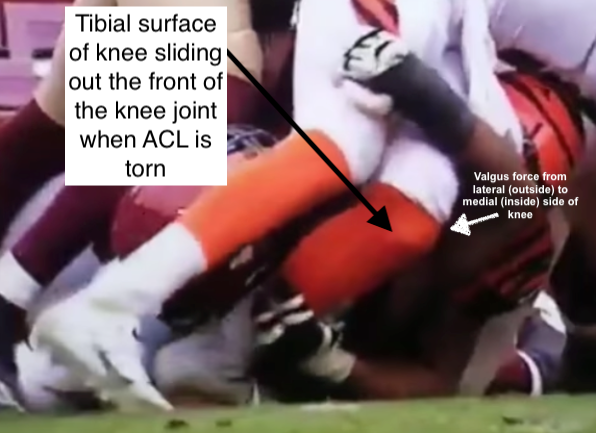

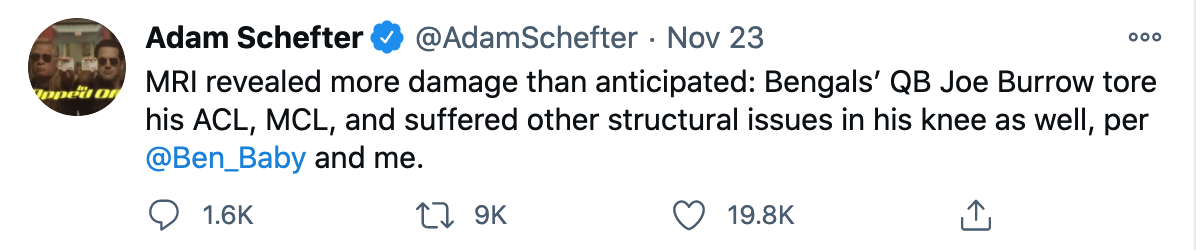

As Joe plants his left leg to throw the ball, he gets hit in the upper body off his right side by Sweat, pushing all of his weight onto his planted, extended, left leg while, at the same time, all of Jonathan Allen’s 6’3” 300lb frame is driven through that planted left knee. Obviously, the knee is not built to handle this kind of stress. The forces on Joe’s knee at that moment were both hyperextension of the knee as well as a severe “valgus stress” – which means force directed from the lateral or “outside of the knee” towards the medial or “inside of the knee.”

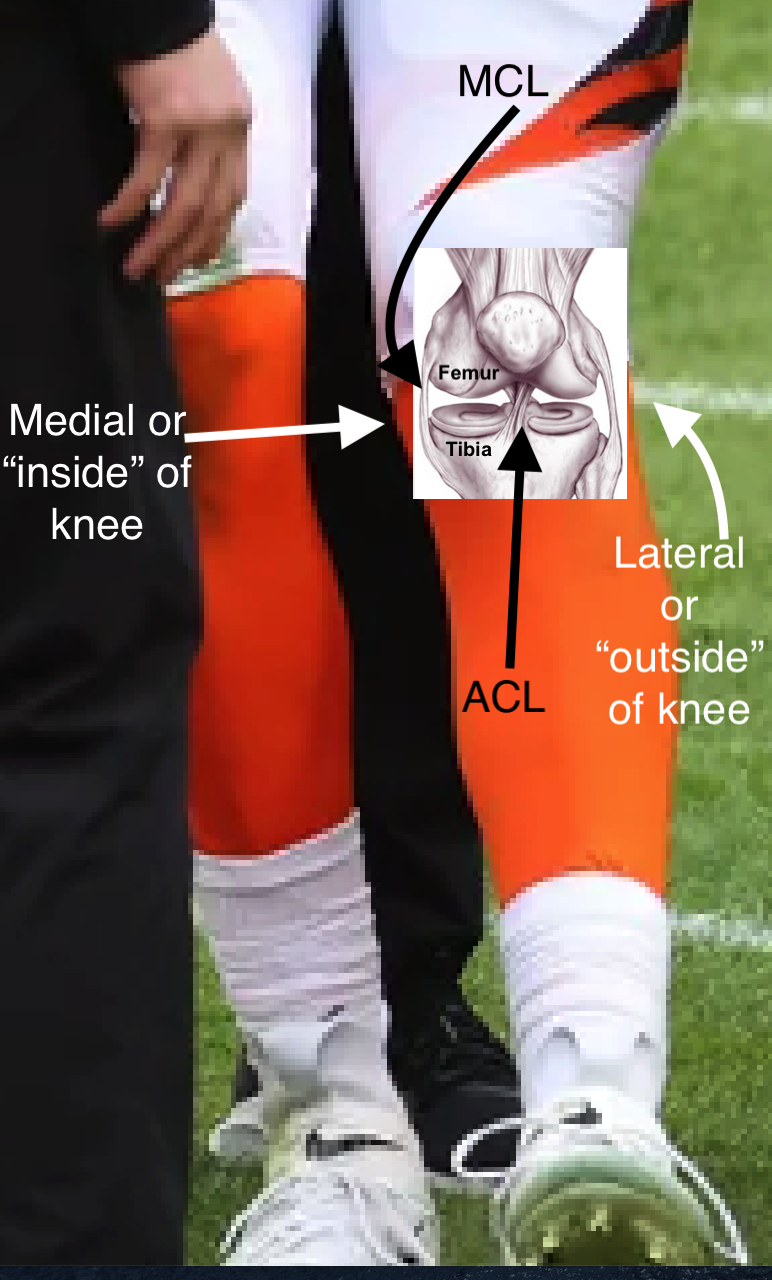

The result of this type of force on the knee is commonly an ACL and MCL tear – which is exactly what Adam Schefter reported that Joe suffered, as well as, “other structural damage” to his left knee.

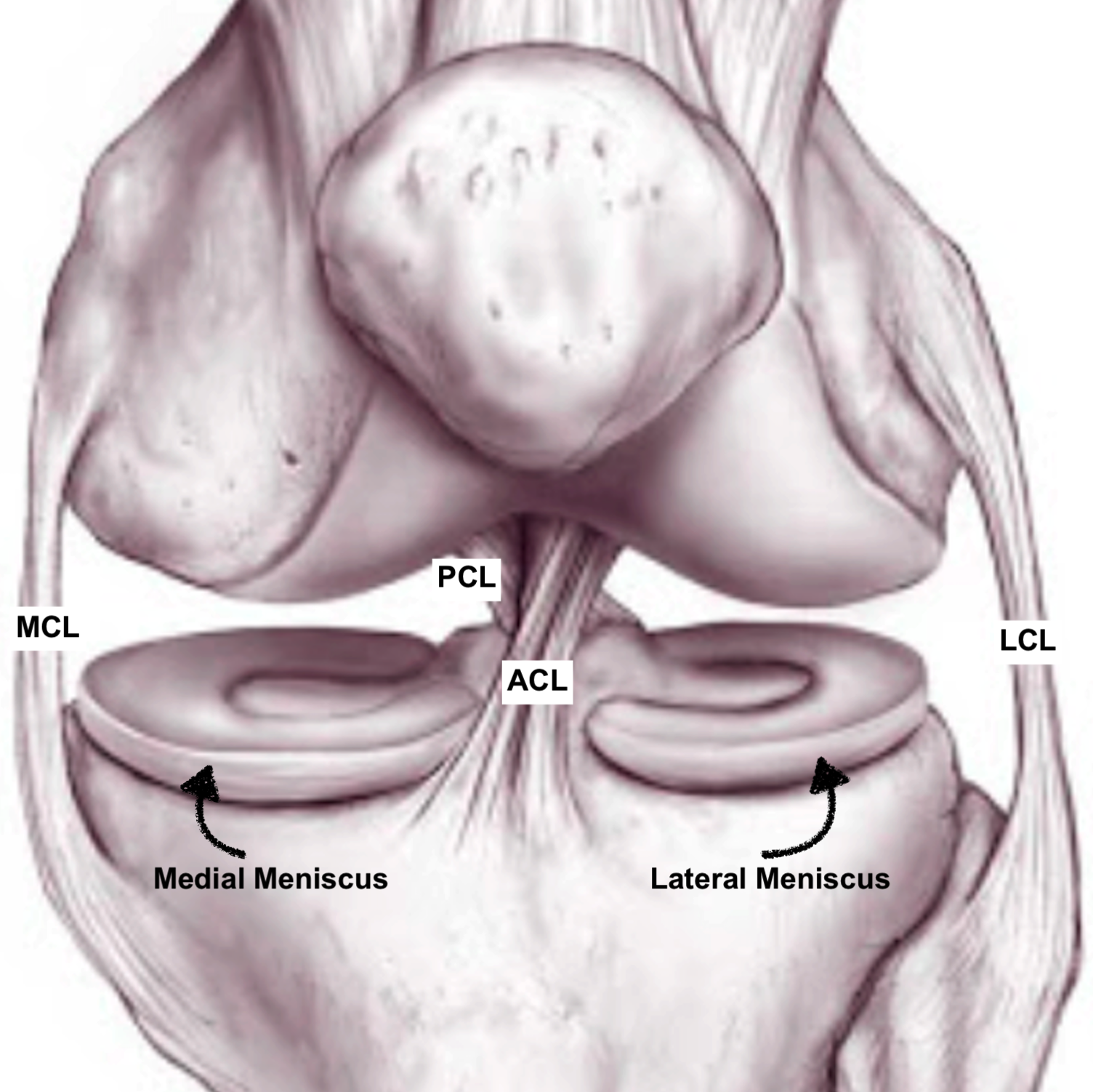

ACL tears are one of the most common sports related knee injuries we see as Sports Orthopedic Surgeons. The ACL, or Anterior Cruciate Ligament, is one of the main stabilizing ligaments in the knee. The four major stabilizing ligaments of the knee are the ACL, the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL), the Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) and the Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL). The two cruciate ligaments, ACL and PCL, (cruciate meaning “cross shaped”) go in opposite directions crossing over each other in the center of the knee and give the knee anterior-posterior or “front to back” stability. The collateral ligaments, MCL and LCL, are found on the sides of the knee and provide varus-valgus or “side to side” stability. The most common “multi-ligamentous” or more than one ligament knee injury in sports is the combined ACL and MCL ligament injury – which is exactly what Joe Burrow suffered.

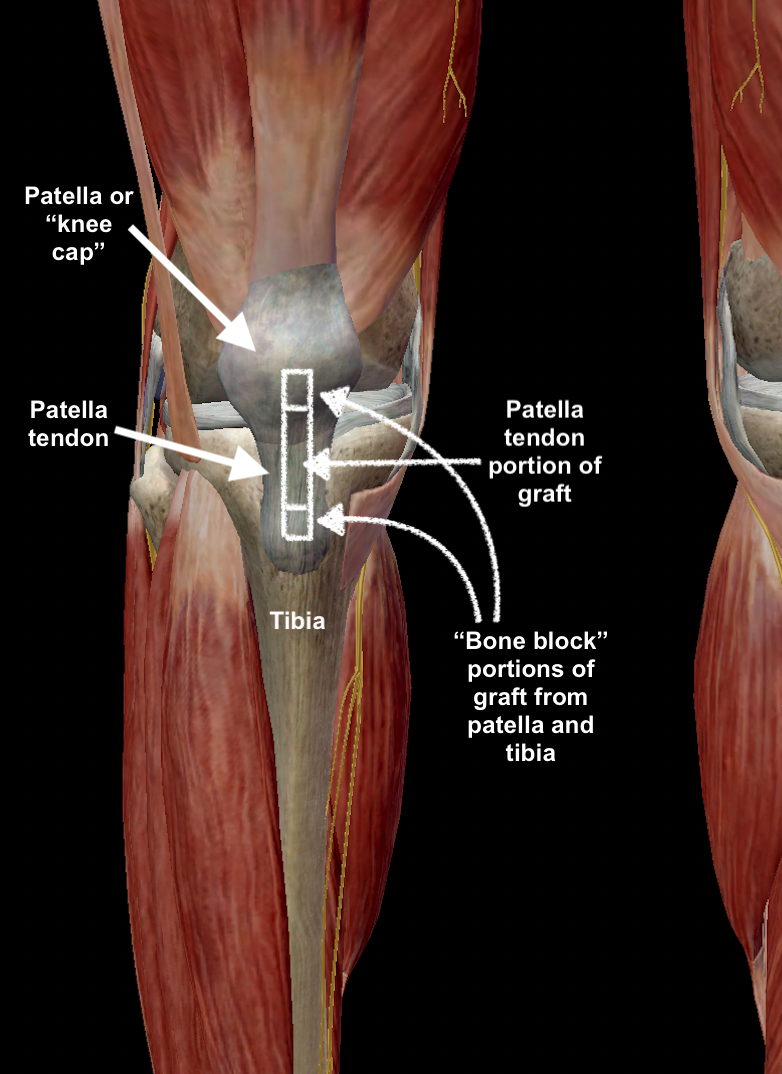

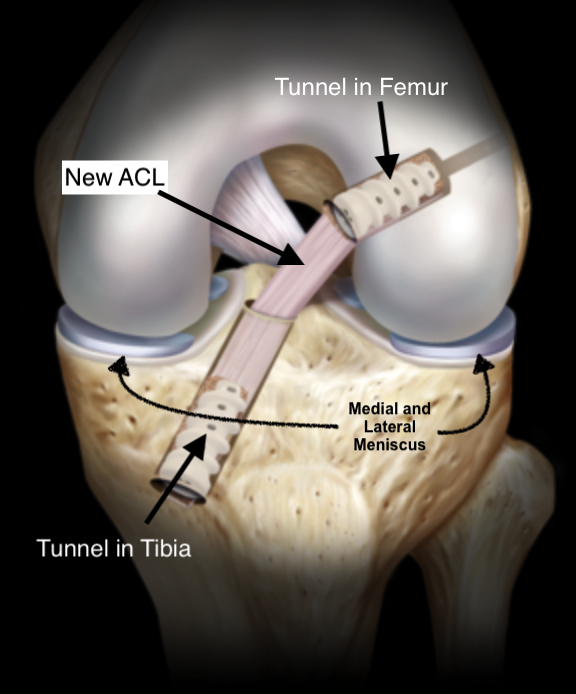

The surgical treatment for an ACL injury is called ACL ligament reconstruction, which means instead of repairing the torn ligament, we surgically build a “new” ACL. The surgery is “arthroscopic” meaning small incisions are used to place an arthroscopic camera inside the knee as well as small tools to carry out the procedure. The most common way of creating a “new ACL,” especially in a young athlete like Joe Burrow, is by using a portion of the patient’s patella tendon. The patella tendon is a tendon that connects your “knee cap” or patella to your Tibia. When using this technique, a portion of the patella tendon is harvested with a small block of bone still attached, on either end of it, from the patella and the tibia – this is called a “Bone-Patella Tendon-Bone autograft” or BTB autograft (autograft means the graft comes from the patient’s own body whereas an allograft means the graft comes from a cadaver). Other graft options include using hamstring tendon autograft or quadriceps tendon autograft. Allograft options from a cadaver include BTB, hamstring tendon, or Achilles tendon among others. All of these options can be very successful. In older patients or patients who are not elite athletes, other graft options may be the best choice depending on the type of method your surgeon utilizes, but the most common graft choice in a young elite athlete is the BTB autograft.

During surgical ACL reconstruction, a hole is drilled in the patient’s tibia (lower leg bone below the knee) that enters the knee joint where the ACL used to attach to the tibia and another hole is drilled through the femur (the “thigh bone”) which also enters the knee joint where the other side of the ACL used to attach to the femur. We then thread the BTB graft through these holes until the patella tendon portion of the graft is inside the knee joint in the same orientation as the old ACL. The bone pieces, or blocks, on each side of the graft reside inside the holes we’ve created in the femur and tibia. This allows for “bone to bone” healing of the bone block portions of the graft inside the tunnels which is a reliable and fairly quick form of healing. The tendon portion of the graft becomes the new “ligament” and will provide both rotational and anterior stability to the knee.

The MCL portion of Joe Burrow’s injury does not always have to be addressed surgically. The treatment depends on how severe the injury is and what other medial sided knee structures are injured. There are several medial sided knee structures that provide stability along with the MCL that can be injured – these include smaller ligaments and hamstring tendons that cross the knee joint on the medial side. This entire complex of structures is often referred to as the “Posteromedial Corner” or “PMC”. If the injury to the medial structures is minor, the treatment can be non-operative and wearing a brace for added stabilization. If the injury is more severe, then surgical options range from repairing the torn ligament or a reconstruction procedure similar to the ACL reconstruction with a graft. Some new techniques of both MCL repair and reconstruction include using an “internal brace” which is essentially a special type of suture, which is included within the repair or reconstruction, which may offer enhanced strength and protection to the new or repaired ligament.

Another very common knee injury is a meniscal tear. The menisci are “C” shaped pieces of cartilage in the knee. There are two menisci in the knee, one on the lateral or “outside” part of the knee and one on the medial or “inside” part of the knee. These pieces of cartilage lie between the tibia and the femur, inside the knee joint, and act as shock absorbers and also provide some element of stability to the knee. During multi-ligamentous injuries, like Joe Burrow’s, one or both of these menisci usually get pinched and twisted between the femur and tibia during the moment of injury and can be torn. Some element of meniscal injury likely encompasses the “other structural issues” reported in Joe Burrow’s injury. Injuries to the meniscus are often treated initially non-operatively with rest and physical therapy. However, in acute injuries, especially when they happen at the same time as injuries to the ligaments of the knee, treatment is usually surgical. Surgical treatment for meniscal tears is done arthroscopically with small incisions for the arthroscopic camera and tools. Surgical treatment options are either “shaving down” the torn portion of meniscus, also called “partial meniscectomy,” or repairing the torn portion of meniscus with sutures. The decision between these two surgical options is usually made intraoperatively when the tear is assessed and is based on location as well as the characteristics of the tear.

The rehabilitation and return to play following ACL reconstruction has received much media attention over the years. Elite athletes are always trying to push the boundaries and return to play as soon as possible – and, as Sports Orthopedic Surgeons, we are also trying to find the safest most efficient ways for athletes to return to play as quickly as possible. Following ACL reconstruction, the average time to return to sport is 9 to 12 months. Elite athletes are usually returning to play closer to the 9-month mark and some push through rehabilitation even quicker and return to play sooner than 9 months. The key to safe return to sport requires a thorough evaluation of the patient’s ability to athletically maneuver safely within their respective sport and positional requirements rather than a strict calendar 9- or 12-month timeline. The athlete usually progresses through each stage of rehabilitation based on physical evaluations by the physical therapist as well as the surgeon. When they’ve progressed through the final stages of rehab, they are usually tested on a variety of movements including single leg hopping and cutting, as well as other sport specific movements, to be evaluated by the surgeon and therapist. When the athlete successfully passes these tests, they are released to return to play without restriction. The major risk of returning too quickly is obviously re-injuring the same knee. However, there is also a high risk of injury to the opposite knee due to altered running and cutting mechanics if they are not fully prepared to return safely. This is why the evaluation of their ability to athletically maneuver with appropriate mechanics prior to full return is so crucial.

Media reports indicate that Joe Burrow will travel to California and have Dr. Neal ElAttrache perform his knee surgery. Dr. ElAttrache is an excellent Sports Orthopedic Surgeon from the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in Los Angeles. Dr. ElAttrache is well known in the field and notably performed Tom Brady’s ACL reconstruction in 2008 and, more recently, Saquon Barkley’s ACL reconstruction earlier this year. After a successful surgical reconstruction by Dr. ElAttrache, dedicated rehabilitation with hard work by Joe and the Bengals’ training staff and with no rehabilitation setbacks, we can hope to see Joe Burrow back under center for the Bengals next September.

Leave a comment